Financial models, plans, forecasts, budgets, whatever you want to call them, are not homework assignments passed down from VCs and board members to test founders and operators on how well they know their businesses. Budgets are not some hurdle that you have to clear in order to keep your job either. If you miss your budget, that’s not the end of the world. However, if you miss your budget and you can’t adequately explain why, that’s when you start to get into some trouble.

In the public markets, the concept of sandbagging is prevalent among CFO’s and managers who are trying to manage expectations. They will provide financial guidance to the investors and analysts so that investors can better understand their business and assess various risks. Frequently, however these managers will provide a forecast that is below what they actually expect, so that when they beat those expectations, they get rewarded in the market. “Wow, look at how good we are actually doing!”. This is not necessarily exactly how it plays out, but generally, public company CFO’s are threading this needle in some respect. If they provide a forecast and not hit it, they can get hammered by public investors. This is very common-sense logic and it makes me glad I am not a public company investor.

Unfortunately, a lot of private company managers take a similar approach. “Let’s be overly conservative so that our investors aren’t pissed if things go awry”. This is terrible logic in the private markets because it completely misses the point of what a budget is supposed to do. [Also, if you have an investor who thinks like this, run!]

A budget is a tool that managers and investors can use to make real-time, strategic decisions on the business. What’s more important than the results of a budget, such as TTM revenue, gross profit, EBITDA, cash at end of period, etc., are the assumptions and drivers backing up these results. Assumptions and drivers can be metrics like ACV, CAC, NRR, etc, but they can also be less measurable things, like “can we hire dev talent at an adequate pace and get the onboarded effectively, or do we need to rethink our process”, or “is my sales team doing a good job of qualifying a pipeline and executing efficiently” or “is my sales cycle 6 months or 9 months”. As you continue to operate your business, you will get more clarity on how close to reality these assumptions really are, and they will help be drivers for your business long term. Also, these assumptions will become more and more specific. Instead of answering how long your average sales cycle is, you will be testing what your sales cycle is for each deal based on various pipeline qualifications, such as industry vertical, internal owner, etc.

Other Driver / Assumption Questions:

You assume that CAC is going to be $50. You hit April and you are finding that CAC is actually $75. This should change how you execute your go-to-market motion, marketing budget and year-end results, among other things.

Your first five deals were all done in 12 weeks. But now you have hired three sales people to accelerate growth. After Q1 closes, you have found that one of them is executing in 12 weeks and the other two are moving things along the pipeline, but it’s taking much longer and haven’t closed a deal yet. Maybe you hired the wrong kind of sales people? Or maybe your process needs improved. Or maybe the one who is executing on the 12 week timeline is a superstar and the others are on a more reasonable timeline. Regardless of reason, this is data you need to be tracking.

Your first 20 deals all came in at $50K ACV or higher at initial outset of the contract. But now, as you scale and have executed on some product strategy shifts, you are finding that initial ACV is only getting closed at $40K, but upsell opportunities are way more common 3 months after first close.

What kind of budgets to put together

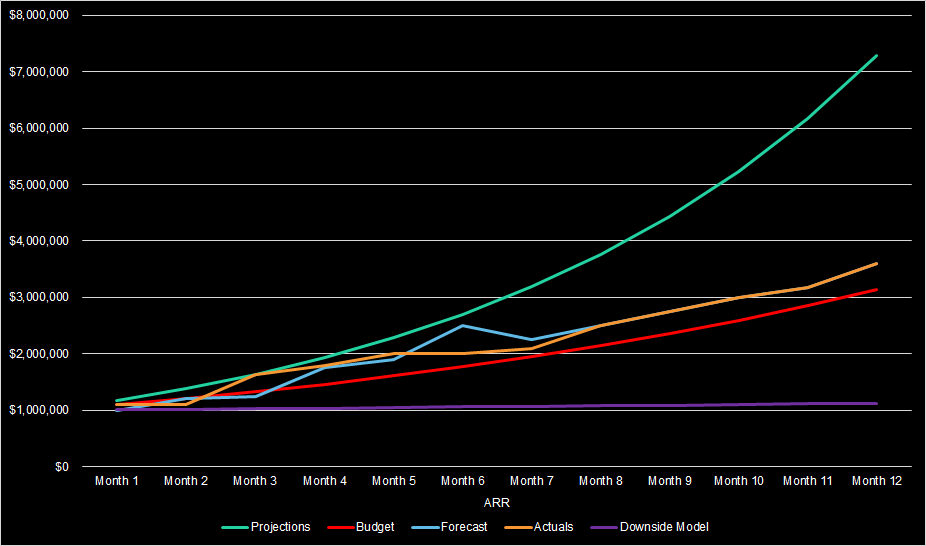

With it in mind that your plan is a tool for your to understand your business better, we recommend putting together four types of budgets:

Projections - optimize for growth. This is the plan you put together to test various growth assumptions. This is the strategy you implement if you are trying to grow at the absolute fastest possible pace - keyword being possible. The assumptions you are likely making here are effective sales cycles, ease of hiring and training, ability to fill up the pipeline adequately, lack of technical issues, upsell ability, etc. This is generally the answer to the question of “What would need to be true for you to 10x revenue / ARR next year?” While this is your “go and get it” plan for sales, it still needs to be grounded in some reality. Like all other budgets, you are testing certain assumptions. If you nail this budget, you know that now is the time to be extremely aggressive and start scaling rapidly. Capital follows growth, so you won’t have any problem finding partners to assist you here.

Budget - This optimizes for cash & growth. How can you still show reasonable growth [2x - 3x over the course of 12 months] while still also giving your company at least 24 months of runway. The point is that you are still growing, but not necessarily trying to take on every risk and assumption all at the same time. Assumptions involved here are tested in shorter bursts and not necessarily all at once. These assumptions typically include customer payment efficiency, ACV, employee retention, customer retention, NRR, etc. This is your default investable model - you need to execute on this in order attract a Series A or B round. This is still hypergrowth but more focused on capital efficiency.

Forecast - This optimizes for feedback. This is what you update every month and/or every quarter. Each month, you need to review your drivers and assumptions and tweak your model based on the output of those figures. For instance, if you think that your initial ACV at the start of the year is going to be $50K, but after February, your initial ACV is coming in at $44K and that seems to be the market rate for your product, then you should update your assumptions for the rest of the year to reduce assumed ACV by $6K. One of the goals of a professional management team is the ability to forecast out a month, a quarter, and a year, with high levels of confidence. At the early-scale stage, your goal should be to dial-in this ability. Use this model to not just feel good about your drivers and assumptions, but to know them front and back.

Downside Case - This optimizes for cash. What are reasonable things that could go wrong? Maybe you have a big customer whose usage of your product has declined in the last couple of months - could they possibly churn? What about a tech build that your product team told you is going to take 3 months, but might actually take 6 if things don’t go well? Let’s bake these crummy outcomes into a model. And then figure out how to make your business model work - headcount reductions, reducing hiring plans, not investing in certain product initiatives, etc. This isn’t your “rainy day” model, it’s your “stormy day” model. Things have gone poorly - now is not the time to roll over!

What does Test Revenue Mean?

Test Revenue is the period in time when the distance between your Forecast budget and actuals slowly comes together. Early on in a startup’s commercialization lifespan, forecasts and actuals will vary widely from one another. That is because a startup is still testing out some of it’s key levers to better understand what is driving their growth. The early scale round is focused on shortening the time it takes to understand these levers and reduce the time it takes to start nailing your forecasts. Use your budget to help you know the assumptions of your business so that when those assumptions change in real time, your expectations can change as well.

Example: expect sales people to bring in $x revenue monthly, but data showing that they only bring in $y for certain types of sales folks. etc. So when you hire someone new, you can have a better feel for how that works.

This is how your budgets look compared to actuals:

THIS IS TEST REVENUE: