I talk to a lot of people every week and tell them what Refinery Ventures does. Most VCs have their own spiel that they rattle off ten times a week. I think mine is pretty good (or maybe I have some form of Stockholm Syndrome) and gets the point across effectively. But I still get plenty of questions about our firm and what we look for in an investment.

What sectors do you focus on? [basically anything that is high growth, high margin, and high-tech]

What size check do you write? [$2 million - $3 million]

Do you have an ownership target? [Not really]

What type of growth do you look for? [hyper]

Do you have any revenue traction minimums before you invest? [no, but we do say that we like companies who are approaching $1 million in ARR]

And I almost never get:

What stage do you invest in?

For the simple reason that I spend most of my opening explanation of Refinery Ventures talking about stage.

That little ditty goes something like this:

We are hyper-focused on a specific stage, which we refer to as Early Scale. Think of Early Scale somewhere on the Seed-to-Series A spectrum. It has less to do with the name of the round in which we invest, and more to do with what the company actually looks like. Companies at this stage typically have (i) traction, (ii) signs of product-market-fit, and (iii) signs of customer-demand-pull (although likely not perfect execution thereof). These companies frequently lack core processes, procedures, and people to really set the stage for hyperscale and hypergrowth. Examples/Symptoms of these areas of potential growth include founder-led hero sales, product-led-growth missing some key features, or a need to double/triple workforce next year and not really knowing how to do that. That’s where we get involved.

The through-line of all of these concepts is that startups at this stage are at a difficult transition period - going from interesting idea and product that might work → to something that people clearly want so badly that now a repeatable business needs to be built around it. Professionalization is a tricky business, regardless of how much demand is present. If a startup scales its business prematurely, it can get burned and even blow up. As a result, a startup needs to continue on it’s growth trajectory while also continuously testing its product / business model / team to ensure that the path it is on is the right one.

My spiel is worth breaking down into component parts.

Seed to Series A Spectrum

There are some firms who still refer to themselves as a “Seed VC” or a “Series A Investor”, but a lot of times, even VC’s stay away from that nomenclature. The reason being: they don’t really mean anything to anyone anymore. There are $60M seed rounds. There are Series A financings that establish companies as unicorns. Remember Quibi? Or how about the fact that a blockchain company in New York raised a $150M SEED ROUND(!) in 2022. That’s ludicrous. And in case you think that is just a symptom of the frothy covid market, there was a company in France that raised a $113M seed found in June 2023.

Of course, if you actually dug into a lot of these enormous, laughable Seed & Series A rounds, you might find wonky transaction dynamics. Or companies that actually have bootstrapped to sizeable traction and hadn’t yet needed financing up to that point. Or some other variable that would make it make sense.

Regardless of context, quantifying a Seed round is a very difficult task to complete. Despite all of this, most seed rounds are pretty standard depending on your geographic location. But if you are located in the Cincinnati and you spend time investing in cities ranging from Chicago to Kansas City to Nashville to Pittsburgh, you realize that seed rounds in different locations can change drastically even in locations just a couple of hours apart. As a result, I do my best to avoid calling any rounds by any of these names. It only starts somewhat normalizing at the Series B level, and even that can be pretty difficult to pin down.

The real difficulty, of course, is benchmarking seed rounds based on traction. 20 years ago, a Series A occurred when a startup reached $1 million in revenue. Today, that benchmark has changed - either going up or down depending on location, business model, margin profile, founder, profile, and a variety of other factors. You might say “Series A” to one person, and they think a company with $2.5M of ARR based in Toronto, or they might think $1M of cARR into a technical AI startup in the Bay Area.

So as a result, we focus less on key benchmarks (although they still matter), and more on traction and repeatability.

Companies at this stage typically have:

Traction - these companies have sold something. Or they have a mass of users actually using their product. Sometimes this traction doesn’t come with revenue, but if the startup is selling software, at this point, they most likely have real customers paying real money to solve real problems. This is important because one of the first things any startup is trying to prove is that they have built something that people want. And the reason startups build things that people want is because that generates money. Money generates cash flow. Cash flow rules everything. As the saying goes, C.R.E.A.M. - CASH RULES EVERYTHING AROUND ME, DOLLA DOLLA BILL Y’ALL. If a startup doesn’t have traction, it’s hard to identify product-market-fit.

Signs of product-market-fit - it’s one thing to get customers to pay a startup for their product, it’s an entirely different thing to show that a decent amount of customers all actually want the same product. That’s the thing about the term product-market-fit - it can frequently be confused by some to mean that customers have the same problem as one-another. But it really is an indicator that customers want the same, identical product as one another. And when that happens, that means that a broader market for this product actually exists. Otherwise, startups don’t really have a product, they have a weirdly focused software development consulting firm. Or something else entirely. The key here is the repeatability. Because if the product can be repeated in a reasonable manner, then it can likely be scaled in a similar manner. And if this is the case, then venture returns may be in reach.

Signs of customer-demand-pull (although likely not perfect execution thereof) - Okay, so a startup has customers paying money for it’s stuff. Not only that, but a bunch of customers are all buying the same product and using it in the same way, indicating that the product the startup has built has a real market. But what happens when potential customers start coming to that startup and demanding that they sell them their product. It’s so dang good that a startup can’t keep up with demand and isn’t even sure where all of these customers are coming from. That’s a problem. A really, really good problem. And it’s customer-demand-pull. A telltale sign that a company is ready for financing.

Another way of thinking about these three characteristics is that they are early proxies for three things that venture capital firms care about: cash flow, scale, and velocity. Traction as a proxy for cash flow, but it also helps validate (on invalidate) that this business will have a high margin profile. This is a critical component of venture as it should unlock cash reinvestment into the business, thus improving capital efficiency.

Product-Market-Fit is a proxy for scale, which is important because venture works best when big opportunities are available. PMF helps establish what kind of customers want this product. And once that is known, then extrapolating to understand the market size is feasible.

Customer-demand-pull is a proxy for velocity. It’s not just about having high margins and a big market, startups raising venture need to do it quickly too. If the problem is so painful that customers are dragging it out of the ecosystem (a lot of early adopters!), then there is a decent chance that the startup can scale really quickly.

Company Lacks Core Processes, Procedures, and People

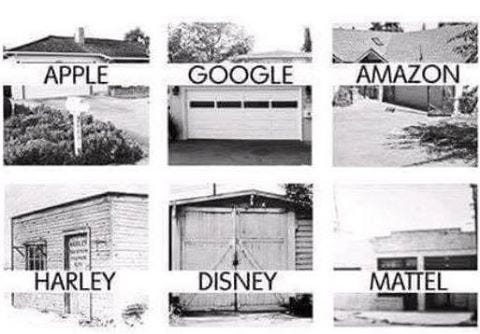

The thing about startups is that they are, by nature, undercapitalized. Of course, this is the whole stratagem - take a little bit of capital and try and turn it into outsized returns. The thing that drives me crazy about mega rounds is that they miss this core component. Startups should be, by nature, capital efficient engines. Everyone has heard of ramen-noodle entrepreneurs because it is a trope, but also because it has serious merit. Everyone who is reading this has seen some version of the hackneyed meme found below. It’s a reminder that many of the great companies of today started out of woodsheds and garages.

But it’s also just reality. Most startups need to start somewhere. But it’s not just about money. Human capital and knowledge capital are critically in short supply at startups as well. Partially because of a lack of monetary capital, but also because the nature of startups means that they are high risk and brand new. These factors make it hard to attract talent and hard to have pre-existing set processes. Maybe you can find good people to work at your new AI startup, but good luck finding folks with 10 years of experience building LLMs. Or selling LLMs. Or doing anything with LLMs.

It’s all brand new, so new processes need to be created. Sometimes there are existing processes that you can lean on as you scale up. Hiring an enterprise software sales team can look remarkably similar across different startups. But even if they are super close, they still have some stark differences. Do you need to hire more junior folks who can “work the phones” more effectively or more senior folks who have a good “rolodex” of names they can already call upon? Or do you need to hire go-to-market people who are better at evangelizing a new solution that is untested in the market? These questions are endless.

The point is that it’s really hard to know what the process should be for any startup. And if a startup scales a bad process too quickly, that can blow things up in a bad way. Hiring 15 BDRs before realizing that 6 sales directors are actually the way to go can be a costly mistake, in time, energy, and money. It becomes the onus of a startup at this stage to identify the right processes, procedures, and people while still growing rapidly. That is very hard to do.

Examples of Signs of Early Scale

Founder-Led Hero Sales: One (if not all) of the founders is the person actually sending cold outreach emails, grinding for sales calls, negotiating deals, and just doing whatever it takes to get a deal across the line. This is important because it can be very expensive to actually hire a sales person or to spend a ton on marketing, regardless of how direct/attributable that marketing actually is. Even in a PLG-environment, a lot of startups in this stage are still pretty hands-on in getting deals closed. While this might seem counter-intuitive, it’s important for founders to deeply understand their customers, their product, and the problem they are solving. There is really no better way of doing that, especially early on, than actually being on a sales call. Startups are exercises in solving problems for money. Talk to the people who you are solving these problems for and try to convince them to give you money and you will inherently learn a lot.

However, that doesn’t really scale. There are only so many founders in a startup. And eventually, startups need to expand beyond just the founder leading all of the sales. And the first thought a lot of folks have is “I am going to hire a head of sales / CRO / VP of Sales and let that person take over our process.” While that is perfectly reasonable thing to think, it comes with some flawed logic. First, most of the work at this stage still involves individual contribution, and many (definitely not all!) VP of Sales / CROs / etc. are less involved in the hand-to-hand combat of sales. These hires like to build teams and processes, but struggle to pick up the phone and make a sale. Second, there is still a lot to learn about the product and market, and the founder still needs to be somewhat involved. Combining both of these concepts, it’s hard to establish a solid process when you are still learning about product and market. As a result, any process that a new sales hire develops is very liable to break / not apply in a very short period of time. Plus, sales at this stage need to be very nimble and active. Any new layer of management can make that difficult.

That last paragraph might seem somewhat nonsensical. Which is sort of the point. Scaling go-to-market beyond the founder is very complicated. It’s where a lot of startups die.

Product-Led Growth Missing Some Features: As stated in the last section, there is always more to learn about a product, even if it feels like there is clear product-market-fit. Even after sales start scaling, there is room for improvement in product. Frequently, the list of features that a startup has on its roadmap at this stage is nearly endless. Determining which ones to build can be tricky. There are a lot of questions to ask, like - will this accelerate sales? Will this feature improve gross margin? Will this feature expand some competitive advantage? Etc.

Many software startups today have some sort of product-led growth strategy. Sometimes that’s the entire go-to-market strategy. Frequently, it’s difficult to fully automate a PLG motion this early on. Sometimes there is still an onboarding call from a customer success employee to make sure new customers understand how to use the product most effectively. Or sometimes an “automated” feature on the backend is being performed by a real person. Sometimes product virality is still being bootstrapped by members of the team, and not generated in an organic way. Regardless, the long-term PLG vision is not quite being achieved, but there are clear signs of it working long-term.

Need to Double / Triple Workforce Next Year: This one is probably pretty self explanatory. It’s effectively the reason venture capital was invented. A startup is growing so quickly that it needs to radically increase it’s pace of hiring. The work is piling up, customers are banging on the door asking for more of that [insert product here], and it seems like something is breaking every day because of the sheer volume of everything. Frankly, if it doesn’t feel like this, it’s probably not a great idea to raise venture capital.

But, if it does feel like this, then venture might be the best path forward. But the trick is that hiring is hard. Hiring people for startups is really hard. It’s not just about finding folks who have experience. More often it has to do with finding folks who can adapt to a rapidly changing environment. For the startups that are out there changing the world or making a dent in the universe or creating a new category, it’s just as important to find an employee who believes in the mission as it is to find someone who has been-there-done-that.

There are a million pitfalls to hiring. It is especially tricky at this stage because the startup is going from scrappy group of true-believers (otherwise, why would they be there?) to merciless group of executors. The only trick is that most of those executors have to also be scrappy and create a lot of processes from scratch, while also staying focused on the main thing. Experimentation can still occur, but the risks start getting a lot higher. Finding people that fit that mold and thread that needle is exceptionally difficult.