Disclaimer: Newsletter and the information contained herein is not intended to be a source of advice or credit analysis with respect to the material presented, and the information and/or documents contained in this website do not constitute investment advice. Opinions contained within this letter are my own and not those of my employer.

I want to make something very clear: I DO NOT LIKE THE TERM “MIDWEST”. It is nonsensical. Something either is or isn’t Midwestern based entirely on your point of view and the audience you are speaking to. But the reality is that even the people who live in the Midwest aren’t exactly sure what to call themselves.

Of course, surveys like the above can be misleading in a lot of different ways. And even if you think about it on a state-by-state level, it can be a little hard to delineate. If you live in Covington, Kentucky, for example, there’s a good chance you identify as midwestern. But if you live in Bowling Green, Kentucky? Or hell, even Lexington, which is only an hour south of Cincinnati? You might be as Southern as they come. Your school is in the SEC, after all.

The real rub here is that the Midwest is one of four regions for the US Census. It has sub regions, like the Great Lakes (which I am far more partial to when referring to the part of the country I live in - not only is it more accurate, but it just sounds fairer). But the Midwest is what gets a lot of attention when it comes to economic studies, investment research, and the like. Technically, it includes: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin.

Anyone who has spent time in most, if not all, of these places, could tell you that they are all fairly unique from one another. The pros and cons are different for each region. We live in a big, heterogeneous country, with a lot of differences, even in places we consider relatively homogeneous. So when I spend a lot of in places like Pittsburgh, Indianapolis, Detroit, and Columbus, I know not to lump those cities together.

But that doesn’t stop me from reading a lot of stuff about how great it is to build a tech company in the Midwest. The punchlines generally include something along the lines of: cost of living. I hate that. Yes, it is nice that I can live here and send my kids to good schools and not feel completely bankrupt, but

I don’t find it to be particularly sustainable - if a lot of people move to the midwest or a big company blows up here, wouldn’t that hurt the cost of living?

Are the right people motivated by cost of living? Don’t we want ambitious, motivated people to live here? Isn’t that what is going to drive our economy forward? San Francisco is a terribly unaffordable place to live and ambitious people move there all of the time.

Cost of Living is inherently a relative number. It is supply & demand economics at play.

I could be wrong, but saying that Cost of Living is a big benefit of the Midwest is like saying you should eat at McDonalds because the food is cheap. Yeah, it’s cheap for a reason! And aren’t there more appealing reasons to be here, from an economic standpoint?

So the question becomes, what is the economic viability of the Midwest? Is this some stodgy, dying region, or a dynamic, interesting place to invest time and resources?

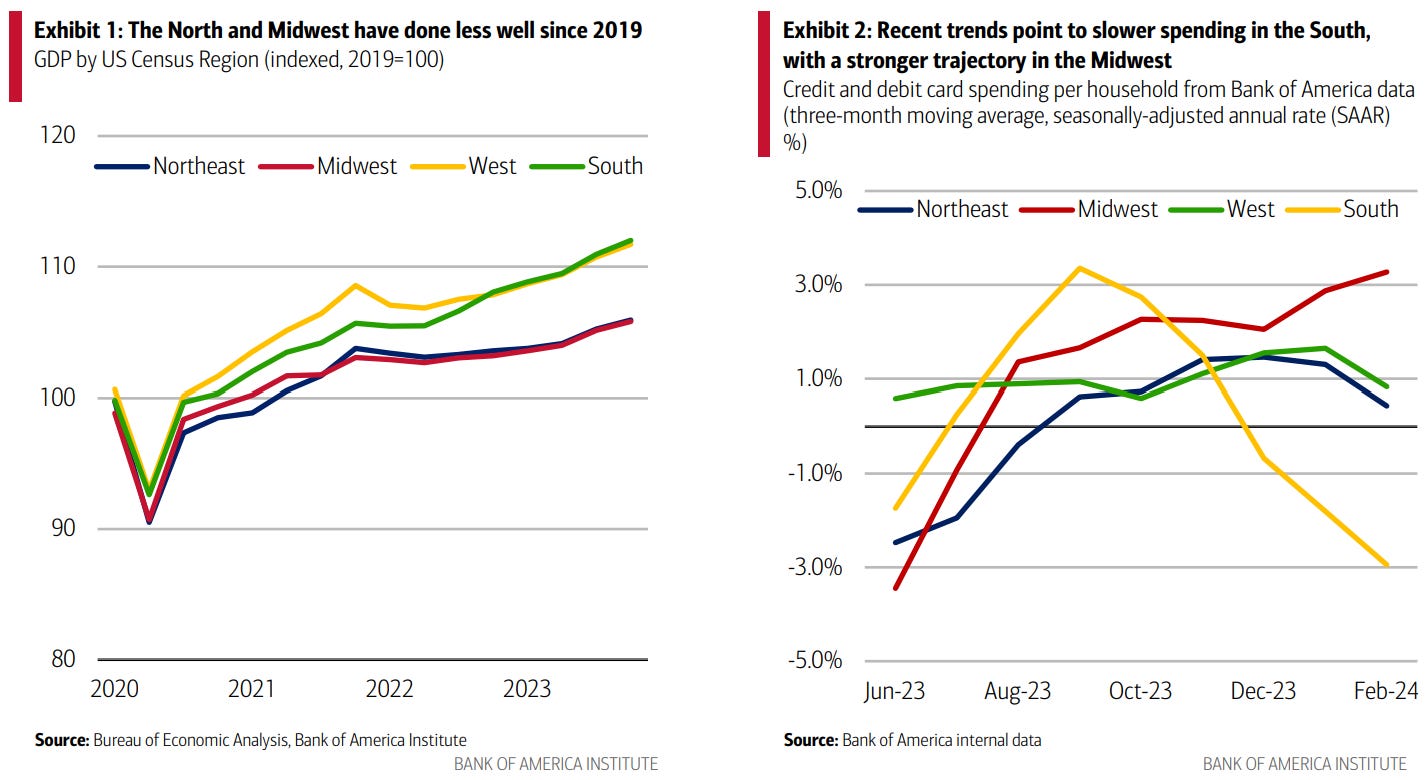

First, let’s just look at the overall GDP performance of the region (see charts below). Post-pandemic, the region has not grown as much as other regions in the country. It isn’t a massive laggard and is following the same trendline broadly, but it hasn’t experienced the bounce back other parts of the country have.

On the flipside, we are seeing some signs that the post-post pandemic slowdown isn’t hitting this region as hard as others either. Spending has slowed in all three other regions, where it continues to tick up in the Midwest.

Depending on exactly how to define the region, the US GDP represents 16-20% of the Country’s entire output. That is relatively on par with the Southeast and the Far West regions of the country. (As an aside, it is pretty cool how economically diverse our country is in general). Ohio and Illinois are the two largest contributors to that figure, but not by a significant margin by any means. To put it in perspective, the Midwest’s GDP, as a standalone entity, would be the third or fourth largest in the world, behind the US and China. It would be larger than Canada, South Korea, and Australia’s economies combined.

Similar to the chart above detailing economic growth in the region post-pandemic, the trendline for GDP growth over a longer time period - three decades, shows it as a laggard behind the rest of the country. Interestingly, post-financial crisis in 2008 / 2009, the region actually bounced back in a better fashion than a lot of the other parts of the country did. Of course, economic data is always very messy, so it’s hard to know what drives this data in general, but the theory is that the challenges in the region’s growth are due to our heavy industrial base and our lack of taking advantage of a technological boom.

The first point carries merit, especially if you look back onto the Midwest’s historical industries and what has happened to our industrial base across the country in general. As the world gets more flat, it’s harder to have industrial companies located in the US. It’s definitely not impossible, but a certain set of conditions need to be met to have a functioning manufacturing business in the USA. And the Midwestern economy used to be largely based on those conditions being easier to be met.

Interestingly, however, a result of that issue is that the region has become fairly economically diverse. Yes, it still doesn’t have a super tech-heavy base (although early signs show that change abounds in that department), most of the Midwest has significant diversification in economic drivers. While the sector used to be heavily dependent upon manufacturing, it could no longer afford to, and so, it diversified in order to stay relevant.

See the chart below for further evidence - there aren’t any slices of that pie that dominate the landscape in Ohio, as an example state. Manufacturing represents ~16% of the Ohio economy, while finance, insurance, and real estate represent ~22%.

Furthermore, 80% of the top Midwest Markets rank among the most diverse in the country, according to Moody’s. This helps to result in the region having the second-lowest unemployment rate, only 10 bps behind the Sun Belt region. Again, 80% of top Midwest Metros have unemployment rates below the national average.

The job market is good in the Midwest. And it’s hard to tell if that’s because the region is growing, the supply of labor is too low, or some other factors. However, over the past thirteen years, ONLY the Midwest has added to its population concentration of 20-34 year olds. And 2024 saw the first year since the pandemic that the region’s population began to grow again.

But this doesn’t necessarily mean that people are moving here in droves. Anecdotally, I am sure most people living in this region will tell you that they know of a lot of folks who have moved back to this part of the country, especially in the wake of the pandemic. In a sense, I am one of those boomeranging types, having moved back to my hometown of Cincinnati in the Fall of 2020. It feels like a lot of people wanted to be closer to home and get out of big coastal cities. But the data doesn’t really support that people are moving here at any accelerated rate. In fact, it looks largely neutral to negative. What’s old is new again: people have been leaving here post-pandemic to seek additional opportunities elsewhere.

However, the truth may be somewhere in the middle. When I was a kid, I remember people talking about the Cincinnati Tractor Beam - referencing the natural pull the city has to people who have left the metro area and want to eventually come back. When I was in college and was working finance internships all throughout town, I frequently would work for folks who had not started their finance careers here, and they would reference the tractor beam. After moving away, meeting fellow Cincinnati expats, and then ultimately returning, I can speak to the truth of that phenomenon. Cincinnati is a GREAT place to live, especially if you grew up here.

Of course, I am biased about the Midwestern pull. I did it, so my confirmation bias is constantly on alert, looking for others who have done it too in order to help me validate my decisions. And likewise, I am constantly looking for justifications about how great of a place to live Cincy is in comparison to other places around the country I could have lived. I simply CANNOT be objective on the matter.

So with that being said, I must state that Cincinnati, and a lot of the rest of the Midwest, are great places to live. Not to raise a family, not to grow a career, not to own property, not to experience culture, nor any other reason that might draw someone to live in a region. The beautiful thing about living in Cincinnati is that you get the opportunity to do ALL of those things, and don’t have to force yourself into any one box or the other. In fact, it would be my contention that you could even do all of those things if you were interested in them.

Unfortunately (or fortunately, depending on your perspective), the data doesn’t exactly prove out that the liveability of places like Cincinnati is a widely held belief. There are a ton of people in this region in general, yes - 1/5th of the entire country’s population is in the Midwest. And not only that, but depending on the metro areas that you are looking at - places like Minneapolis and Columbus and Indianapolis - they are growing at a pretty strong clip - at least faster than the national average. Additionally, the prime working age groups are all growing as well in a lot of the key Midwestern Markets. It’s not just one or two cities that are attracting this growth, like in some regions, but 10 of them, if not more.

But the growth isn’t exactly eye popping. And post-pandemic, the growth story is a little more mixed. Some states, like Illinois, have experienced significant outbound migration post-pandemic, with a net migration loss of ~115,000 people, moving largely to Florida or neighboring states. But on the flip side, cities like Indianapolis and their surrounding metros are experiencing positive net migration growth. There was a general rural boom that occurred in 2021, that has largely slowed down or reversed after 2022. While this doesn’t necessarily mean that people are moving in or out of the Midwest, it does further evidence that the region’s growth story from a population perspective is somewhat of a mixed bag. There are great success stories, and some places that seem stagnant.

However, this could be viewed as a good thing. The Midwestern economy is diverse, and part of the reason its population charts aren’t changing that much is because it is a relatively stable region. If one industry suffers, another might be doing exceptionally well.

The region also has very strong technical talent. While I promise this isn’t a blog specifically about why you should invest venture money in the Midwest, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that we have a strong research and development ecosystem, inclusive of the people actually doing that work. And not just software engineering talent either. We have some of the best, largest, and most prolific research institutions in the world, producing some top tier technical talent at an impressive clip.

Fourteen of the top Fifty research institutions in the country are in the Midwest based on R&D expenditures. Sure, the amount of money isn’t a perfect proxy for research talent and capabilities, but the way grant funding works, it’s not a terrible proxy either. Compared to our population and GDP share, this shows that the region still punches above its weight. Additionally, three of the top ten undergraduate software engineering programs are in the Midwest (Carnegie Mellon #1, Illinois #5, Purdue #10).

Of course, a big question is whether that talent will stay in the region after it graduates and is done with research. And it’s a great question - something that has been plaguing this part of the country for a while. In fact, when I was in college, I was recruited to attend the University of Cincinnati explicitly as part of a program that existed to prevent the “Brain Drain”.

I was studied finance, so it was hard for me to find a finance job in the Midwest, let alone in Cincinnati. I had to travel to Charlotte, NC to find something that worked for me, and almost all of my interviews were outside of the city. It took me 5+ years, but I eventually came back (tractor beam, fully operational).

Now, I am really glad I got that experience and moved away for a bit, because of how much I learned. But I am also recognizing how lucky I am that I was able to find my way back here. There are a lot of folks from the region who would do the same thing, but are just looking for the right opportunity. We hope at Refinery Ventures that we can provide that sort of opportunity.

While I don’t have a super-strong conclusion about the state of the Midwestern economy, one of my core beliefs is that investment firms and entrepreneurs can have a massive impact on the regional outcomes of economic growth. Economic growth doesn’t happen to a region. People impact change in a region and that can drive growth. There are some factors that are out of our control, of course, but I think we generally underrate how much of this stuff is in the hands of the do-ers, the action-takers. So the punchline is that the economic viability of the Midwest is largely dependent upon the actions of the people who live in the region. If we, as residents of the Midwest, want the region to succeed - cities like Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Madison, Kansas City, etc. - it is up to the residents of those fine cities to make that happen.

Very well-written and researched article. As someone who has lived in several midwest cities (Cincinnati, Columbus, Madison, and now Cleveland) as well as San Francisco and works in tech/running a business, thinking about the economic viability of this region is interesting. Most of the companies I work with are actually based in SF or NY but I really want to work with more midwestern companies and subsequently have been trying to get more involved in the local tech scene more these past few years. It is definitely growing, but very different from the coastal cities (as you stated, less ambition) and I've personally found it more challenging to be hired by these companies.