Disclaimer: Newsletter and the information contained herein is not intended to be a source of advice or credit analysis with respect to the material presented, and the information and/or documents contained in this website do not constitute investment advice. Opinions contained within this letter are my own and not those of my employer.

I used to think that the old adage “buy low, sell high” was a form of finance meme because of how ludicrously obvious it was. People would say it jokingly because that is the entire point of investing - it’s so clearly baked into everything an investor does, whether you are discovering value or creating value. It’s like saying that in order to win a game of basketball, your strategy should be to “get more points than the other team”. It’s unnecessary and lacks insight.

My current role aside, there seemed to be a belief in every finance circle I have ever spent time in that cheap assets are good because that means they have only one way to go: up. Eventually the market will correct it’s mispricing and you will be rewarded accordingly. This belief isn’t necessarily ubiquitous - the whole firm or peer group or network doesn’t think that way - but it is pervasive when it’s time to actually review a deal. “I really like this one, but that price is just too high!” Depending on your perspective (a public markets one), you could view what I just described as value investing. An investing style that folks on twitter would lead you to believe is a long-lost money-losing strategy. And while that may broadly be true since the mid-2000’s, I don’t think the core beliefs of value-investing have been shed from the finance community’s consciousness.

When I worked in banking, my whole job was focused on underwriting a deal, figuring out how we could maximize bank profit while still getting the deal done, and poking holes in investment theses. I spent my time thinking about downside risk. When I started in venture capital, I learned a valuable lesson: don’t ask what could go wrong, instead ask what could go right. It’s a simple shift in mindset that is necessary when getting into an asset class like VC - you have to be optimistic to make things work. Ideas mostly sound stupid at stage zero and early companies are by definition ugly. You have to find ways to believe in products, people, and markets, otherwise you will never find a deal to do. Nearly every VC I met and worked with had an attitude focused around the future. In their minds, things were only going to get better.

(Of course, it’s easy for VC’s to be optimistic about individual deals. The entire premise of most VC’s business model is that most of their investments will go to zero. So even if things don’t work out, it’s not a big deal. Whereas with bankers, when one of their deals go to zero, that’s not a good thing. They can have a couple of losers, but when things go straight to zero, things get ugly.)

But what surprised me about VC is that despite an optimistic attitude that permeated the industry, folks still stressed out about high valuations. Everyone I knew talked about how frothy the market was (ironically late 2018 does not hold a candle to early 2021) and how hard it was to value a company. This seemed at odds with a driving mindset that things were going to get better, and there was always more money to be made. From my vantage point, it seemed as if folks felt that the market was acting irrationally and that would be corrected eventually. Of course, people still put money to work because that’s the name of the game - but they did it with a grimace on their faces - “oh wow, I can’t believe I am paying this much for that company!”.

In other words, everyone wanted to buy low and sell high, but could only buy high and hope to sell higher. A cynic would say this is the greater fool theory at work, something that has been going on for a twelve year bull market.

What would an optimist say? They might posit that we are living through a multi-generational shift in technology that can only be compared to the Industrial Revolution in size and scope. Compounded that with the fact that ease of access to information has made understanding and participating in the financial markets at a proficient level more possible than ever. We have only just started to scratch the surface of what is possible with and because of the internet. Industries won’t just be disrupted - whole new value sets are going to be created. As a result, the valuations we are looking at right now will be puny in comparison. Remember, Marc Andreessen, when he got to Silicon Valley in the early 90’s thought that he had already missed the boat.

As an aspiring optimist, I believe most of that. But, still, back down here on Earth, isn’t it a little ludicrous that there are very popular tech stocks currently trading at 50x price-to-sales ratios (and I am not even talking about meme-stocks)? Eventually, exuberance runs out. But how can you tell when exuberance becomes irrational?

Let’s take a look at one of those 50x sales companies and see where things have gotten out of hand.

SHOPIFY

If you have been paying any attention to anything at all over the past year, there’s a decent chance you are familiar with Shopify’s rise to glory. The company, a former startup darling based in Canada (one of those tech entities so big it’s really based everywhere), is the software platform of choice for ecommerce brands. They are the tool you use if you want to launch (or improve) your own online store. But it’s not just for small mom & pop ecommerce companies - brands like Nestle, Pepsi, Kraft Heinz, and Tesla use Shopify to power their stores.

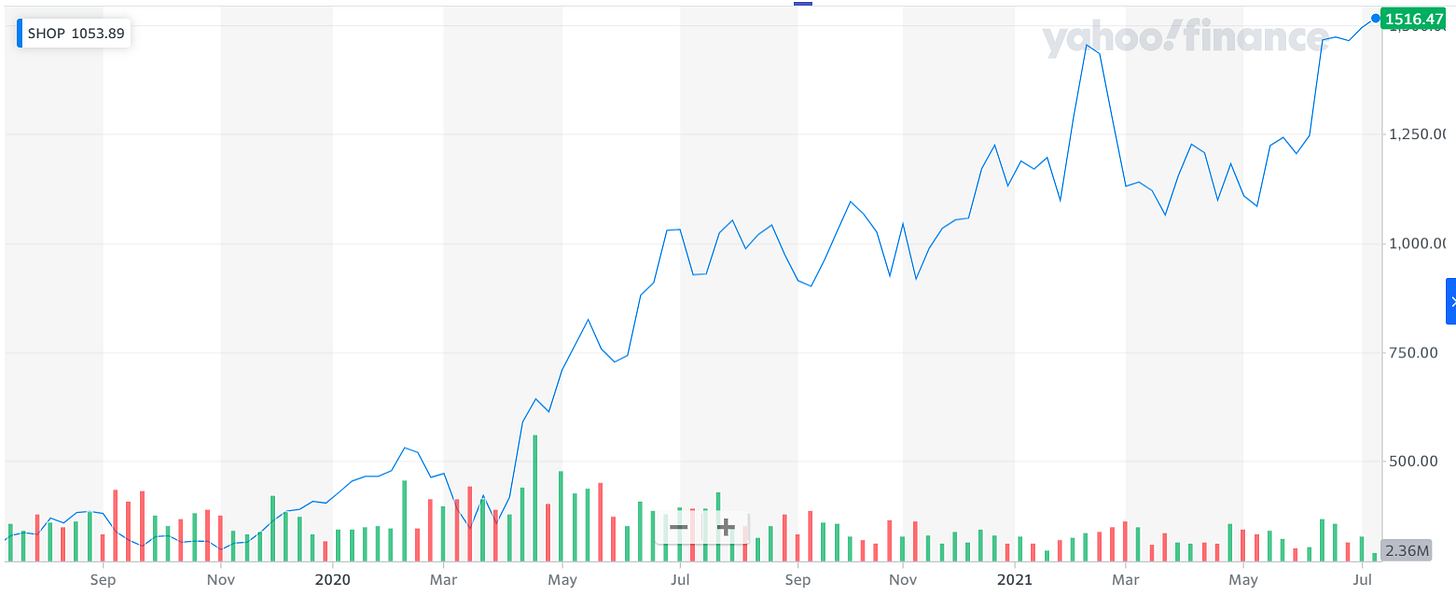

Their revenue growth has been on a tear as of late, almost doubling every year since 2017, reaching TTM revenue of $3.8 billion in June 2021. The Company has been cash flow positive since 2019 (albeit on the back of some serious financing magic) and turned a net profit in 2020. Growth + profitability has been a powerful story on the street for the past couple of years, and Shopify is doing a magnificent job of weaving that tale. Such an awesome job that their current price-to-sales ratio is 56.2x as of their most recent earnings release. To put that in perspective, even banana-land meme stock Tesla has a 20.4x Price-to-Sales ratio - during some of Elon’s crazier runs, they got above 50x, but only during peak EV mania.

But SHOP didn’t just get to this point because they are growing like bananas and turning a profit, although that’s a huge piece of the puzzle. They are also riding an incredible wave - the ecommerce explosion. For years, it felt like everyone was talking about how ecommerce was going to take over all of the economy. And while that hasn’t really happened yet, COVID-19 has shown that there is still a lot of room for growth in that sector. Of course, Amazon has been on the leading edge of that growth with 38% of all ecommerce spend in the US, but Shopify is not far behind with 8%.

Ecommerce as a whole exploded in 2020, but the growth prior to that was still pretty impressive. As the online shopping experience gets easier, more products go online, more customers go online, and the financial security of shopping online continues to improve, that is not slowing down any time soon. There is potential that ecommerce reaches it’s ceiling at some point. But things folks thought you would never buy online, like a car or a house, are now being sold via internet regularly.

But this isn’t an ecommerce-focused blog. The point is Shopify, whose valuation multiple looks obscene, is not only growing quickly and executing very well, they also have a ton of tailwinds to move them forward. Should their valuation multiple carry any flaws, it has very little to do with the Company itself and more to do with the market, writ-large.

And while I have my guesses about what’s going on in the market today, I have a strong conviction that betting against it over the long-term is a bad idea. Shopify is a long-term bet. Betting against it is almost like a bet against ecommerce itself, something I could never have enough conviction to do myself.

Shopify has 11% of global ecommerce market share. 8% of everything purchased on the internet in the US last year was bought on a Shopify-hosted store. Since inception (which wasn’t that long ago!), Shopify has contributed $319 billion in economic activity worldwide. Shopify is a critical piece of the online marketplace infrastructure, and they are only getting started. It’s hard to bet against them.

So the question is about understanding risk. The problem I have had with Tesla is that most of the bull cases to back up their valuation have to do with an absurd number of cars going electric and an absurd number of those electric cars being Tesla, the high-end version of that sector. There are a lot of unlikely things that need to happen in order for that to make sense. But for Shopify? The bull case is basically that the ongoing march toward ecommerce economic dominance continues on its current trajectory, one that has been in super-growth mode for two decades plus. Does any of that seem unlikely to you?

There are plenty of bear cases with Shopify - competition, execution, market dynamics, etc. all could wipe out this giant. But they seem to be at least in the number 2 position riding a wave of internet fueled transition from brick & mortar to ecommerce, maybe the most radical change to our global economy in several decades. The risk gets lessened every day and COVID didn’t hurt their chances either. It might be exuberance, but I am not sure it’s irrational.

Sometimes the market gathers irrational exuberance, and runs up a price beyond comprehension (read: $GME) and for no proper reason (read: $AMC). But other times the winner is so obvious that everyone in the market can’t miss it. I am not sure the path ecommerce will take to achieve world dominance, but I am pretty sure SHOP is going to be a tool in that crusade.

But to be clear: this isn’t a blog just about Shopify either. I have toyed with buying Shopify for a couple of years, but have never pulled the trigger. It just always seemed so expensive. But the point wasn’t about the price I was paying, but about the risk associated. When evaluating an asset, part of the equation needs to include recognizing a low-risk, high reward situation. Sometimes you have to pay up in order to take some risk off the table. This may seem counterintuitive, but if the last ten years of FAANMG pricing has taught us anything - it’s that it’s true.

The flip-side can also be true: just because something is low-priced, doesn’t mean it is low risk. Having a low multiple doesn’t inherently reduce your risk - in fact, it’s the market participant’s job to figure out how to get paid adequately for said risk, not the market’s job to tell you whose risk level is low. That’s one of the biggest fallacy’s with the buy low, sell high attitude - when something is trading at a low level, in public or private markets, it generally is doing that because there is a lot of risk associated with it. Once it starts trading at a higher level, a lot of that risk has been replaced. So instead of looking for something at a low price, look for something that can ride a wave. Tailwinds are your friend, it’s just your job to recognize them.