Disclaimer: Newsletter and the information contained herein is not intended to be a source of advice or credit analysis with respect to the material presented, and the information and/or documents contained in this website do not constitute investment advice. Opinions contained within this letter are my own and not those of my employer.

Ask almost any private equity professional, and they will tell you about the importance of EBITDA - Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization. This ever-sacred number is the lingua franca of the investing world. It is the short hand metric off which almost anyone in the industry can understand any company. When I tell someone about the type of businesses I invest in, the first thing I tell them is the EBITDA range ($1 - $5 million) because that can help convey the size checks my firm writes, the maturity of the companies we invest in, and the types of service providers I typically tend to work with. At times it feels as though EBITDA has become the one, true metric that all other financial metrics bow down to.

It has become that way for several reasons, but the top two are likely (i) it is actually a decent proxy for pre-investment cash flows and (ii) it is so broadly accepted that it has become like the USD - the reserve currency of metrics that could actually mean nothing, but still be accepted by everyone because it carries so much cache. EBITDA is simultaneously a fiat metric and a useful commodity metric.

The Capex Question

Regarding its use as a proxy for cash flow, I think there are a lot of folks who would take some level of issue with that description, but the key word here is proxy. EBITDA definitely has deficiencies - as Warren Buffett likes to say “Does management think the Tooth Fairy pays for capex?” The underlying point of the Oracle’s apocryphal comment: there are a lot of cash expenses that are not picked up in EBITDA calculations that can have a significant impact on “cash flow”. If you are a big industrial printer, you typically have to invest heavily every year into your machines and equipment just to keep the status quo. Your EBITDA number might tell you that you had a great year, but the reality is that none of those cash flows went into anybody’s pocket because it all had to be reinvested into the company. Thus, the lack of capex acknowledgement is one of the chief complaints with EBITDA.

But if we take a step back and really think about capex and its relationship to cash flows, it’s important to keep in mind that not all capital expenditures are created equal. There is some capex that a company has to make in order to keep the business relevant. When you think about investing in new equipment for an industrial manufacturer, what has to be done versus what should be done can sometimes feel black and white. You might have to buy a new machine because if you don’t, the old one will break down and you won’t be able to keep up with demand. This is maintenance capex. Alternatively, the same company might buy a new machine because they are trying to enter into a new market. This is growth capex. Depending on who you are talking to, growth capex is not necessarily part of the free cash flow conversation because it is a discretionary investment. Yes the money goes out the door, but it has some long-term effect and ROI that will, in theory, balance things out and bring in additional future cash flows. Plus, if you are acquiring a business and end up making the Capex decisions yourself, you will have say and control over discretionary investments like that.

An analogy I have heard in the past used to describe growth capex is the idea that it is the Russian Nesting Doll of investment decisions. If an investor is looking to make an investment into a business, part of that investment decision needs to be understanding growth prospects. Growth capex already undertaken by said business was an investment decision made the management of the company. So review of one investment requires reviewing a nested investment and making sure that it has a good ROI. The same could be said for a lot of one-time “EBITDA Adjustments”, but capex is the best example of this idea that a company is a portfolio of investments within a larger investment opportunity. On the flip-side, maintenance capex is needed to keep the lights on, and as a result should be viewed nearly the same as COGS - an essential part of the company’s business model.

So we have established that it’s fair to strip out capex from EBITDA as a proxy for cash flow because there is so much nuance in how that money gets spent. But does that mean that all EBITDA is viewed the same? Certainly not.

The nuances within capex spend (and other below the line items) are picked up in EBITDA multiples in the sense that industries with higher capex requirements are typically valued at lower multiples than industries with lower capex requirements. While this contains shreds of truth, even that requires a some amount of nuance as companies with high-capex-spending peers might run well below their industry average, but might not be rewarded or punished one way or another. Maybe those laggards should be spending more on capex and are letting their equipment deteriorate at a detrimental rate. Or maybe they are making big investments into bad areas and are bad capital allocators. In order to really understand this, investors have to really dig into a business - this is where the craft of investing takes lead over the science.

Other Cash Flow Measures

So is capex the only business investment choice that is viewed as separate from a company’s cash flow proxy? What about non-capex level investments, such as one-time R&D expenses that aren’t capitalized? What about an investment into a sales team in a business with a long sales cycle? Surely these investments are granted some leeway in the investment community, just like capital expenditures? A lot of companies make investments into their business that go above the line and are discretionary, strategic decisions. But if they are being recognized by EBITDA as deleterious to the value of the business, how does that make any sense?

If you are a low capex-intensive business, you are likely going to want to make investments that aren’t picked up in the PP&E line - it doesn’t make sense to buy a bunch of heavy machinery if you are a marketing agency. If people make your product and you want to launch new/better product, you need to invest in people. When these investments are made, they also have a payback period, and don’t necessarily pay for themselves right away. As a result, margins might get compressed and even top line revenue might hurt. So when a business makes and investment, the financial health of said business might start showing signs for concern. But this might lead one to believe that investments in businesses that are not capitalized would be discouraged because absolute EBITDA or EBITDA margin might take a hit. And in some circles, that is certainly the case - managers optimize for short term cash metrics at the detriment of making investments into their business units and product lines.

But there are some industries that welcome non-capitalized investments with open arms. Company’s are frequently afforded the right to be in growth mode because they are owned by investors who are willing to be patient (sometimes too patient!) with the business model and trust their management team. A playbook exists for that kind of growth spend.

Where EBITDA Doesn’t Rule

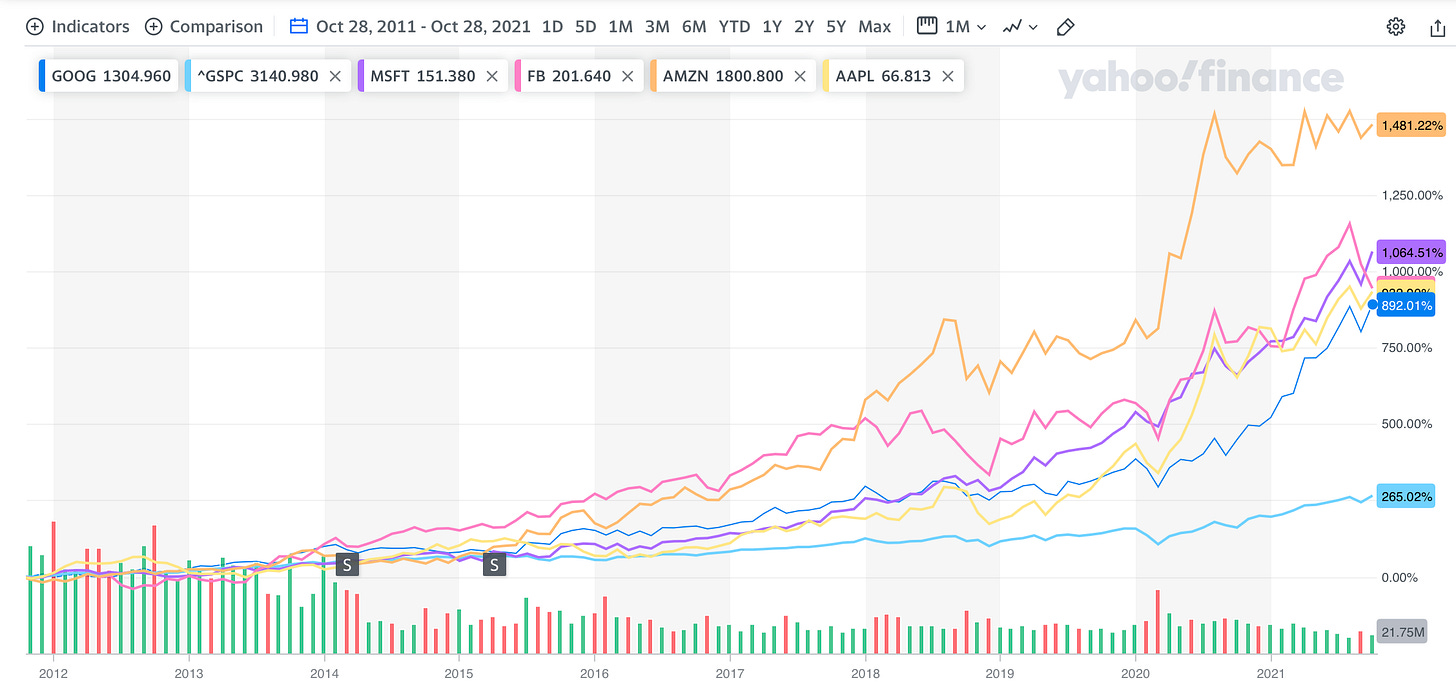

EBITDA is the one true ruling metric for all businesses in the industrial sector. It is the dominant force for valuation in many small caps and mid-cap public equities. For a lot of middle market private businesses, it’s the most important thing on a company’s prepared financials that investment analysts will look for. Even for FAAMG (GAMMA?) companies their EBITDA multiples all tend to line up how you would expect in a market like this. They are elevated compared to most of their peers, as investors pay some premium for excellence, but generally they seem to be a good comp set for one another. This is actually one of the better examples of EBITDA working.

EV/EBITDA Metrics:

GOOG: 19.6x

AAPL: 22.0x

AMZN: 26.3x

MSFT: 25.2x

FB: 15.2x

HOWEVER.

For the Company’s that have seen the most ridiculous growth over the past several years, EBITDA is borderline meaningless. Their EBITDA multiples are all out of whack and don’t seem to correlate to anything else in the market. Some of them do not even optimize their financial results for strong EBITDA performance!

TSLA: 160x

SHOP: 46x

TWLO: -83x

NFLX: 16x (wait, what?)

CRM: 74x

There can only be one explanation: the market is broken. These companies have trash EBITDA metrics yet have dominated the S&P 500 for ~a half decade or more. Those aren’t just fun little startups. Those are largely members of the Fortune top 50. They are massive entities, employing hundreds of thousands of people. They reshape the way that we live and work and play. They have a meaningful impact on everyday life and have changed our society (for better or worse). And one of them is trading at a negative eighty-three EBITDA multiple.

Maybe it is time to hang up the EBITDA metric because it is clearly missing something in the market that everyone else sees. These companies should be getting slaughtered because the one, true metric is upside-down, yet, somehow, they are not. Some of them have been high-returning stalwarts for the past decade.

Maybe the EBITDA metric is great, except for instances where it falls apart. Generally, most of the companies in our second cohort above have a variety of things in common, such as growth rate, tech reliance, subscription-based revenues. But equites, even tech stocks, are still valued based on their ability to produce future cash flows. Despite what some might tell you future cash flow still rules. And all of those companies (as well as a bunch of others), are actively, at least according to them, reinvesting capital above the line, in non-CAPEX level investments and trying build businesses that are unstoppable, much like some of the companies in the first cohort.

Non-capitalized expenditure investment is being valued greatly by the public market, so long as it is actually fostering real growth. And what would normally be picked up in depreciation and amortization add-backs in an old-school company, is completely missed by an EBITDA value in the go-go stocks of the current era. There are probably plenty of reasons for this, but I think structurally, one of the underlying themes for shift from capitalized investment to P&L investment is the broader shift in the US economy. We have gone from an industrial economy to a services and technology focused economy. It’s much easier to make high capex investments in an industrial company than it is in a tech company, a recruiting firm, or some other services business.

GAMMA-like companies reinvested their cash to solidify their market positions at the expense of a strong EBITDA figure and as a result are now kings of the road. Ultimately, the market has decided that it has seen the story enough times and is now actively rewarding companies that are run this way. It’s been a while, but it wasn’t too long ago that Amazon and Facebook’s EBITDA multiples were pretty out of whack. But those companies were reinvesting appropriately and now are being interviewed frequently by Congress because their financial positions are so strong/powerful. The Market is looking for the next company that will get interviewed by Elizabeth Warren in a committee meeting. [I should note that I don’t think all of the companies I listed are doing a good job reinvesting cash flow. Some of them probably just have the market fooled. It wouldn’t be the first time the market was wrong about something like that. It also wouldn’t be the first time I was wrong, either.]

But most of the companies that I have listed out seem to be the exception, not the rule. EBITDA is still a target metric, even though it clearly has some deficiencies depending on the business model or the company’s appetite to reinvest into its business model.

The Path Forward

So if this means that EBITDA multiples don’t make sense for some new age economy businesses, then should we use something different?

It’s probably not that simple. EBITDA still works for the vast majority of companies. I don’t see a day where it stops being so important for private equity investors any time soon. But we should stop being blown away when a company who is trying to radically alter a market or has some revolutionary technology or is in an industry that is ripping has an out-of-whack multiple. Instead, we need to investigate how warranted that bloated multiple really is and how much that company is investing into it’s business. We also need to recognize that for some industries, a compressed EBITDA margin is not necessarily a bad thing, if that means a company is using its cash to build a better business.

There was a point in time (mid-1990s) when Wal-Mart was notorious for having negative free cash flow. This was because WMT was heavily investing into expansion and growing it’s business. It was aggressive in its investment plan for retail domination. It eventually won the big box store competition, but that was not always something that everyone took for granted. During this same period, the company’s stock was relatively flat. The market didn’t realize that the investments Wal-Mart was making at the time would lead to such an impregnable position. Now the company is an absolute cash cow and has changed the way investors think about a retail investment strategy.

Wal-Mart’s playbook is now common knowledge, but that wasn’t always the case. The same could be said for Netflix or Amazon - those cash reinvestment playbooks have become much more mainstream and accepted in the market today. There are probably dozens of other investment strategies that are currently being tested right now that the market has yet to believe in. That’s where the real opportunity awaits.

In summary, EBITDA is still the one, true king. It is the acronym that runs the world. It is applied effectively for a lot of different types of business models (basically all of the ones I am investing in professionally). But it still has its faults. While it is easy to write-off a business because it has a crazy high EBITDA multiple, it’s good to keep in mind that EBITDA doesn’t always tell the whole story. It might think it’s the king, but it still has a long way to go.